[ad_1]

In light of worsening mental health among youth, strategies have been implemented to improve access to behavioral health services in recent years, including expanding school-based care for students. School-based behavioral health services can improve access to care and allow for early identification and treatment of mental health issues. However, challenges such as funding and workforce shortages often hinder implementation and sustainability of these services. Further, although 96% of public schools offered at least some mental health services in the 2021-2022 school year, only 12% strongly agreed that they could effectively provide mental health services to all students in need.

Leveraging Medicaid to improve and address gaps in school-based behavioral health services has been a key strategy in recent years as youth mental health concerns have grown. Medicaid provides significant financing for the delivery of these school services and provides coverage to approximately 4 in 10 children nationwide. School-based behavioral health programs may rely on Medicaid in several ways, including reimbursement for medically necessary services that are part of a student with a disability’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP), for eligible health services for students with Medicaid coverage, and for some administrative activities. Recent guidance states that Medicaid spending for school-based health services in 2021 was nearly $6 billion. Provisions from the Safer Communities Act of 2022 utilize Medicaid to expand both school-based health care and other mechanisms of youth behavioral health care in several ways, including:

- Requiring the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to provide states with guidance on how to support and expand school-based health care, including mental health services.

- Awarding $50 million in planning grants to states to create and/or build out school-based health services.

- Improving the implementation of Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment benefit across states.

This issue brief explores the implementation of these provisions from the Safer Communities Act thus far, with a focus on the guidance issued from CMS. While the guidance is complex and covers a wide array of services, this analysis focuses on provisions related to behavioral health services (i.e. services for mental health and substance use disorders). This guidance is the first updated Medicaid guidance on school-based services in nearly 20 years and provides detailed information on ways to make payments for school-based services and reduce administrative burden. Additionally, this brief highlights other, recent federal initiatives that may impact youth behavioral health care access in schools.

How does the recent guidance from CMS address access to behavioral health care in schools?

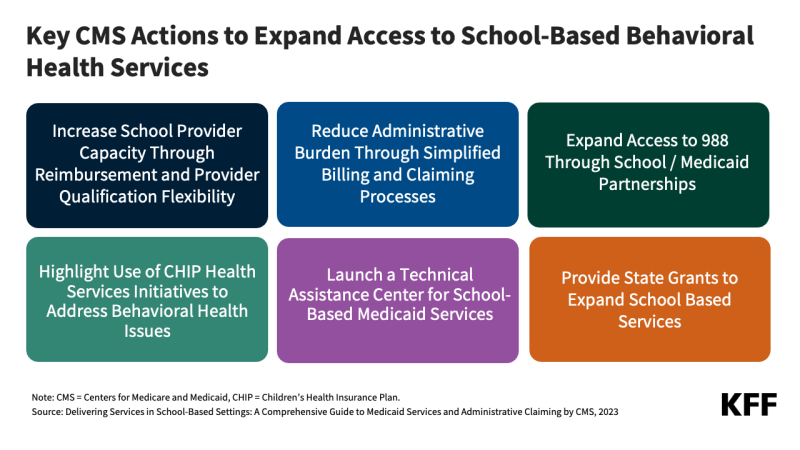

CMS issued new guidance on school-based health services in 2022 and 2023; this updated guidance highlights the importance of providing behavioral health services to students. The goal of the updated guidance is to increase access to school-based health services and to decrease the administrative burden schools face when delivering services through Medicaid. The guidance provides an overview of services that can be offered in schools and how those services can be delivered; outlines flexibilities in billing, documentation, and claiming practices; and updates provider qualification requirements. Medicaid may cover a range of health services provided to children in schools including health screening services, speech or physical therapy for children with disabilities, and a range of medically necessary physical, mental health, and SUD services. Specific behavioral health services including psychological testing and evaluation, individual and group therapy, and behavioral health crisis services. The guidance does not expand upon services covered but clarifies what is covered and how schools can most efficiently deliver them under Medicaid. The guidance encourages state Medicaid agencies to coordinate with state education agencies and schools to facilitate school-based services and announces opportunities for technical assistance. Finally, the guidance explicitly states the advantages of providing behavioral health services in schools, noting that school-based behavioral health services are linked to improved access to mental health treatment, fewer disciplinary actions, and higher graduation rates among students. The guidance aims to facilitate increased school provider capacity through 1) opportunities for higher reimbursement rates and 2) broadening the provider qualification requirements. Historically, reimbursement rates for school-based services could not exceed rates for the same services offered in a community setting. However, the updated guidance highlights opportunities in which the reimbursement for school-based services may be higher than the community reimbursement rate due to additional costs associated with operating in a school environment. Rates would be at the regular Medicaid match rate and must still be consistent with Medicaid rules that require payments to be consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care. The ability to pay school-based providers higher rates may be a strategy for schools to build out and/or retain providers, as seen in South Carolina in 2022. Additionally, the guidance says that states have the flexibility to determine which providers of school-based services will be covered and to establish minimum provider qualifications that may differ from qualifications for non-school based services. The guidance provides the example that states provide counseling services by school social workers who may not be able to provide such services outside of a school setting because they lack the required credentials. These changes aim to mitigate widespread behavioral health provider shortages for youth.

The guidance aims to facilitate increased school provider capacity through 1) opportunities for higher reimbursement rates and 2) broadening the provider qualification requirements. Historically, reimbursement rates for school-based services could not exceed rates for the same services offered in a community setting. However, the updated guidance highlights opportunities in which the reimbursement for school-based services may be higher than the community reimbursement rate due to additional costs associated with operating in a school environment. Rates would be at the regular Medicaid match rate and must still be consistent with Medicaid rules that require payments to be consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care. The ability to pay school-based providers higher rates may be a strategy for schools to build out and/or retain providers, as seen in South Carolina in 2022. Additionally, the guidance says that states have the flexibility to determine which providers of school-based services will be covered and to establish minimum provider qualifications that may differ from qualifications for non-school based services. The guidance provides the example that states provide counseling services by school social workers who may not be able to provide such services outside of a school setting because they lack the required credentials. These changes aim to mitigate widespread behavioral health provider shortages for youth.

With the intention of reducing administrative burden, the updated guidance offers simplified methods and clarifications on billing and claiming processes. Medicaid claiming and payment practices pose an administrative burden on schools and may impact their ability to provide and sustain health services (including for behavioral health) for students. For example, the Reconciled Cost Methodology is a common route of reimbursement; however, it requires multiple steps including careful documentation of covered services provided to Medicaid-enrolled students and determining interim payments throughout the year to allow for appropriate cash flow. The updated guidance offers detailed information for each step and provides examples for states to take into consideration. Random Moment Time Studies – a method used to determine the amount of time schools spend on Medicaid-covered services and administrative activities – are also time consuming, complex, and require detailed documentation. The updated guidance eases this process in several ways, including greatly reducing the number of times these studies must be completed by staff.

The guidance specifies coverage of interprofessional consultants and the ability to expand access to 988. Interprofessional consultations expand access to specialty care and foster interdisciplinary input on patient care. In the context of schools, a school-based provider could consult with a specialty provider about a student’s needs and bill the consulting provider’s time to Medicaid. In the past, consulting providers were not covered by Medicaid since the patient would not be present. In addition, the guidance specifies that state Medicaid agencies and schools can partner to expand the use of 988 for students experiencing suicidal ideation, issues with substance use, and/or mental health crisis, or any other kind of emotional distress.

The guidance highlights opportunities to use CHIP behavioral health benefits, including Health Services Initiatives to address mental health and substance use. CHIP behavioral health benefits include screenings, preventive services, therapy, and treatments such as medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorders and tobacco cessation services. Health Services Initiatives (HSIs) allow states to use a portion of CHIP funds to improve the health of low-income children, including their mental health. HSIs can include coverage of direct care or broader public health measures. For example, New York currently has an HSI for providing and training school staff with naloxone kits to prevent overdose-related deaths for students. Nevada previously had an HSI covering mental health services in after-school programs for high-risk students.

As indicated in the guidance, CMS, in partnership with the Department of Education, launched a Technical Assistance Center for school-based Medicaid services. The intention of the center is to help schools – particularly schools in rural areas – and state Medicaid programs implement and expand school-based services in a variety of ways, including navigating complex Medicaid billing practices. The center has so far hosted webinars covering topics such as service implementation and evaluation processes, developing payment methodologies, and recommendations for engaging local education agencies. The center recently published FAQs that offer information on topics such as requirements for submitting state plan amendments and billing.

In 2024, CMS opened applications for state-level grants totaling $50 million to be used toward expanding school-based services. CMS anticipates that 20 states will receive $2.5 million over three years from the grant funding. At least 10 of the awarded grants will be marked for states that currently do not cover school-based services for all children enrolled in Medicaid. CMS anticipates that funds will be awarded by this summer. The $2.5 million of funds is modest but provides a mechanism for states to obtain additional administrative resources that will lead to greater access and coverage of school-based services.

Even with the implementation of Medicaid-related provisions from the Safer Communities Act, some barriers to expanding Medicaid school-based services remain. For example, there is no mechanism in place for schools to easily identify which students are eligible for services (i.e., which students are enrolled in Medicaid).

What other recent measures leverage Medicaid for behavioral health care access among children?

CMS guidance from 2022 summarizes existing resources and provides examples of ways to leverage funding and expand access to mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) services through the Early Periodic Screening Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit and how this extends to school-based services. This Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services (CMCS) Informational Bulletin also provides State Medicaid Agencies, agencies administering the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), state behavioral health agencies, state developmental disability agencies, and other stakeholders with relevant existing federal guidance and examples on ways that Medicaid and CHIP funding, alone or in tandem with funding from other federal programs of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), can be used in the provision of high-quality behavioral health services to children and youth. CMCS remains committed to providing information and technical assistance on leveraging funding opportunities to optimize beneficiary access to needed.

The guidance provides various strategies to expand and strengthen behavioral health services for children with Medicaid. Under EPSDT, states may cover services even for students who do not have an existing mental health/SUD diagnosis. EPSDT extends to prevention, screening, assessment, and treatment for behavioral health conditions without fixed limits on coverage. The 2022 guidance cites examples of state efforts to increase behavioral health screenings and school-based services; for example, in Arizona, Michigan, and Georgia. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act requires federal agencies to review EPSDT implementation and provide updated guidance for state Medicaid programs by June 2024 and requires review and updated guidance every five years thereafter.

In 2024, CMS released new guidance on how state Medicaid agencies can further adopt broad telehealth coverage to improve access to care in schools. CMS highlighted three states as examples of best practices for delivering Medicaid school-based health services, including behavioral health services.

- Colorado‘s website with information on billing for school-based services includes procedure codes for telehealth services, including tele-behavioral health services.

- New Mexico provides a list of facilities that can serve as an originating site for a telehealth visit, including school-based health centers.

- Washington offers a School-Based Health Care Services Program Billing Guide that includes information on which originating sites are covered for telehealth services for students with disabilities. Information for providers billing services for students without disabilities can be found in the states’ Telemedicine Policy and Billing Guide.

Outside of Medicaid, other provisions from the Safer Communities Act address access to children’s behavioral health services. Provisions include providing trauma care to students, expanding the number of school-based mental health providers, and funding additional school programming. SAMHSA has awarded $74 million to Project AWARE, a program to develop mental health support and trauma care in schools. As of February 2024, the Department of Education distributed more than $571 million to increase the training and hiring of school-based mental health professionals. The Biden Administration’s proposed budget for FY 2025 includes $200 million from the Safer Communities Act to increase the number of mental health professionals in schools. President Biden’s proposed budget also adds $19 million to the CDC’s Leadership Exchange for Adolescent Health Promotion initiative, which develops plans for school-based services focused on behavioral health.

This work was supported in part by Well Being Trust. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

[ad_2]

Source link